Does a brand still mean anything in news?

Ezra Klein bubbled up a provocative question and raised some good points in his recent piece “Is the media becoming a wire service?” In the Age of Distribution, the news body seems destined to be increasingly disconnected from the news head. It seems quaint to actually go to a news-branded site to read that company’s take on the news of the day. Instead, Flipboard flips it to us. Messaging services like Snapchat surprise even themselves by becoming “platforms”. Facebook (Instant Articles) and Apple (News) want in on the action, and who knows how Alphabet will rearrange the letters N-E-W-S?

But Klein’s questions of disconnection reminded me of a finding I’d heard from numerous publishers, but one I hadn’t written much about: the enduring value of native apps. Even as the mobile browser’s utility has multiplied with readers’ shift to smartphones, the native app remains a potent traffic driver. In fact, as some of news brands’ most loyal (and most paying) readers pile up minutes on iOS and Android apps, we may see the native app join with the open web as one-two punch helping define the next generation of the news business.

Andrew Lipsman is one who has been noticing this phenomenon for awhile, and speaking to groups about it.

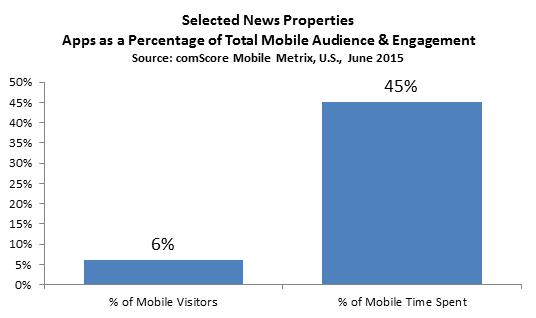

Lipsman, comScore’s vice president for marketing and insights, analyzed some data for me. The results: While only 8 percent of those accessing news on smartphones and tablets use apps, they account for 45 percent of all mobile time spent on news. That’s a huge differential, more than five times what we would see if app usage and mobile browser usage were the same. Those eye-popping numbers derive from a selected group of 25 top legacy and digital-only U.S. news publishers, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, BuzzFeed, Gawker, Vice, Vox, Fox News, and CNN.

“There’s your loyalty,” he told me. “It’s a power law distribution, the Pareto principle,” he says. That references what many in business call the 80/20 rule, where 80 percent of the effects come from 20 percent of the causes. While well established, we hear too much from news publishers about their big number of unique visitors — and too little about what their core readership is doing.

At The Wall Street Journal, “apps wins by a factor of about 3 to 1” compared to the mobile browser in time spent, says Edward Roussel, chief innovation officer of Dow Jones. Users of the Journal’s smartphone apps, iOS and Android, consume about 18 pageviews per session; on its tablet apps, the average is about 24.

What’s going on here? Is it the utility of apps, or the psychology of apps, or some mix?

Roussel looks at the app as a place for depth, the browser the landing pad for breadth (What are they thinking? WSJ mobile aims for breadth and depth“).

On the one hand, WSJ.com mobile browser is the place where you have the most promiscuous traffic — so I send you a link, you pick it up on your phone, and you click into it, and you read one article, and drop. The mobile browser on a smartphone at this point is a convenience. You can get the article, you can share it, you can read it, someone emails it to you…conversely, the app experience on mobile is the place where you discover engagement. It’s a destination…You’re more likely to stay.

It’s simply about habit. The habit that we have is that if I tweet a story, and it pops up on your phone, if I email you a story across your phone, then the chances are you’re on the go, and you’re more likely to open it up in the browser in your phone. It appears to be the case that the reading habit in the web browser is a convenience that allows you to access information on the go.

So does the mobile browser = like and the app = love?

“It’s interesting, because we do do consumer groups and when you get on the topic of apps, people get a lot more passionate,” says Roussel. “They hate it if you screw things up…and they love it if you fix it…We figure that their passion is that they hate it — or it could be that they love it — but they are a lot more passionate about apps then they are about the browser experience. There’s an intimacy with an app. It’s on your phone and you’ve got limited space, and so it’s an honor to be an app on someone’s phone — because they’ve made space for you in the device that’s most personal to them.”

For those sites charging for access — the legacy news sites — we do see a higher usage of apps among paying subscribers. That’s not a huge surprise: Subscribers should be those most brand-identified, skewing older and maybe liking the sense that they’ve bought something — an icon from a store — and aren’t simply paying for a service. As Roussel suggests, that app notion is a little bit more physical, offering a whiff of ownership. We need someone like behavioral psychologist Dan Ariely to experiment with the (ir)rationality of appiness.

As Roussel has led the year-long, ground-floor-up redevelopment of the Journal’s apps, he’s found himself neck-deep in numbers. “The usage is overwhelmingly subscription,” he says. “I’d estimate 15 percent of people [using the apps] are non-subscribers who are testing it out.”

The app consensus — and big numbers

In talking to a variety of publishers, I heard a surprising near-unanimity about the engagement power of apps.

At the Financial Times, two-thirds of app users are subscribers, according to FT.com managing director Jon Slade. Then the big number: “They generate 96 percent of the pageviews.” In fact, the FT now plans its future development, in strong part, in understanding the proclivities of its two major groups of mobile readers.

At The New York Times, the experience is similar. About 1.7 million unique visitors use its iPhone app monthly. Forty-eight percent of them — or about 800,000 — are heavy, engaged readers, defined as coming back to the Times four or more times per month. Many of them are subscribers; the Times targets the ones that aren’t with offers to finally open their wallets. On the iPad, that great newspaper-loving instrument, 48 percent of all iPad users — that’s 439,000 out of 900,000 monthly — are “engaged.”

As The Washington Post increasingly takes on the Times (“Is The Washington Post closing in on the Times?”), apps are one weapon. At the Post, engagement time on apps beats browser three to one.

But it’s not just a paying-subscriber-to-legacy-media phenomenon.

At Business Insider, the insurgent (and free) business site, “average time spent on the iPhone app is more than four times the average time spent on the mobile web,” Julie Hansen, BI’s COO tells me (here’s an interview with Hansen). Of those using the app, only 8 percent come less than once per day. In fact, “the majority of sessions are from the 200+ number of sessions a month bucket.” By contrast, she says, only a small fraction of sessions on the desktop and on the mobile browser come from among those heavy users.

“BI’s apps are entirely focused on overserving the loyal users who access them daily,” says Hansen. That means better understanding — and serving — the loyalists. “The features built into the app are for power users, such as offline use, saving articles, search.”

For Bloomberg, the numbers top even BI’s. For its apps — these are Bloomberg’s consumer apps, which are largely free to access, not its professional ones — apps outrun browser usage ten to one. On the mobile browser, that’s 3.3 minutes per visitor. On Bloomberg apps: 33.8 minutes.

At KPCC, public radio’s best-staffed regional news station, apps drive the same kind of loyalty. While it counts only one unique visitor per month via app for every 17 via the browser, 72 percent of those iPhone app users are making return visits. Via the browser, only 34 percent of the audience has recently visited.

Alex Schaffert, Southern California Public Radio’s director of digital media, puts a public media spin on the app/browser question: “The aspiration for maximum reach should be driven by mission [of public service]; the bigger financial opportunity is to serve loyal users.”

Take one other company, what at this point could be considered a $1 billion “startup.” Vox Media got this valuation as NBCU invested $200 million last week, doubling down in its digital media bets as it put another $200 million into BuzzFeed.

Vox Media used to have a couple of native apps, for SB Nation (sports) and The Verge (tech), but abandoned those in 2012.

“If the goal is to better serve our readers, shouldn’t we be able to provide value to all my users?” says Trei Brundett, who has served as Vox’s VP of product and tech since 2008. Brundett says those early Vox apps topped at about 1.5 percent of all monthly users. He saw his development staff too focused on the apps and not enough on mobile generally. Coincidental with the termination of the two apps three years ago, Brundett says he pointed the whole staff, now numbering 100 of Vox’s 400 employees, at mobile. “We saw the rise of mobile early,” he says. “The whole organization changed. We no longer had a ‘mobile’ team. It was everyone’s problem.”

All that said, Brundett is emphatically not anti-app. “I can guarantee 100 percent you that Vox will have a native app some time in the future,” he told me. He also declares himself a big fan of The New York Times’ apps, liking the company’s willingness to experiment and learn.

Our takeaways

So what do we make of these numbers?

Clearly, there’s a market to be served, and my sense is that it can exploited and expanded.

In part, publishers must understand the role of generation and age here. Newspaper apps indeed do pull in an older demographic. “Thirty-five to 54-year-olds have the highest relative usage of newspaper apps,” Lipsman told me. Millennials underindex for use of newspaper apps, though they overindex for use of general news apps. General news includes both the big newspaper brands, like the Times, Journal and Post, and the Huffington Posts, BuzzFeeds, and Vices.

In other words, native apps aren’t just for older readers.

In general — for the Internet in general, not just news — apps far outpace mobile browsers in time spent. Fully 87 percent of time spent on mobile is spent in apps, only 13 percent in the mobile browser.

Further translation: If you want to lay a claim to engagement, the app’s the thing — no matter how convenient a browser may be as a link receiver.

While Vox’s Brundett makes excellent points — and has the traffic to back them up — I like the both/and (rather than either/or) strategy that I see in these app/browser questions. It’s noteworthy that most of the apps noted here, and in that top 25, come out of national or national/global news companies. Those companies both have the resources and longer-term perspective to put a both/and strategy into place, while many regional publishers offer underpowered apps, if any at all. An underpowered app won’t get on your customer’s first screen, and that’s the real estate that most matters in this mobile age.

comScore’s Lipsman makes an intriguing point here, applicable most to those publishers who will have a tough time getting to that first screen.

“It creates a chicken, egg scenario,” he says. For publishers “not investing in the app and the utility of it, those numbers are going to cycle downward…if you’re small enough the question is, ‘We have limited resources, do we design for mobile web or app since we can’t do both?’ Actually, what I tell a lot of people is, despite how important the app is in aggregate, the correct answer for most business is probably focusing on the mobile web…Unless you get some great, sweet distribution deal, which a niche brand isn’t going to be able to do, then it’s ultimately up to the user’s choice. Whether they put that app on their phone, and then whether it gets real estate where they’re going to use it. They’re just not going to download so many different apps.”

For most major national news brands with adequate resources, doing both makes sense. For national niche news players, maybe Lipsman is right about mobile browser first. Then there are the daily newspaper companies. Can they hope to be important enough — and good enough — for their readers to earn a first-screen icon? I think it’s key to their survival in a mostly mobile world.

For publishers aiming to really play in this new world, it’s a double both/and. Not only creating great app and browser experiences — but also the best on-app, on-site experience any publisher can muster — and the best off-site (Apple News, Facebook Instant Articles, etc.) experience they can create. Ezra Klein’s point is a good one:

But even now, the rules around off-platform distribution constrain innovation in quiet ways…There are lots of these little quirks hidden in the distribution system, and they quietly, but surely, enforce a status quo bias across the industry. That isn’t because Facebook, Google, or anyone else is trying to staunch innovation — it’s just because these services can’t possibly be built to support every new idea.

So fast-forward three years. Imagine it’s not just distribution. Now every article has to work in the publishing systems built by Facebook, Apple, Snapchat, Flipboard, mobile app developers, and so on. Even if these systems are great — and, in many cases, they will be — they’re not all going to be the same. A lowest common denominator effect will set in quickly: The pieces with the highest possible audience will be the pieces that work across the most platforms. So it won’t make much sense to pump endless energy into innovative, custom articles. Why spend so much of your time on a piece or a format that will only be available to a fraction of your audience?

He’s right to ring a small alarm. But there’s a lot we don’t yet know about the nature of this evolving distribution-is-all ecosystem. We don’t know how brands, formats, and experience can play out in others’ playgrounds. I’d like to see Vox join with the legacy publishers in pushing the big distributors to allow for the kind of creativity Klein rightly advocates. That said — one way or the other, publishers will have to adapt. If they want the huge audiences that off-site distribution and the mobile browser make possible, they need to invest in that development. And if they want to do a deep, deep job of satisfying those core, brand-loving readers, they must create even better app experiences over the next couple of years.